Nick Hornby is a good flirt. Not that he’s flirting with me when we meet at the cafe on the top floor of 5 Carlos Place— the newly renovated Mayfair townhouse acquired by MatchesFashion.com to showcase exclusive retail installations, spotlight up-and-coming designers,

and generally manifest the covetable wardrobe of a fashion insider—but he’s throwing around his boyish charm like the French throw sneers at tourists. That is to say, he’s fully aware of what he’s doing, and is not désolé at all.

He understands the power of a gregarious smile, the lasting impression of intentional eye contact and the flattery of research. “You were just in California for the Apple Keynote. And I saw on Instagram that you love fashion. How are you enjoying London?” It’s the appeal of focused attention. It’s the allure of good manners.

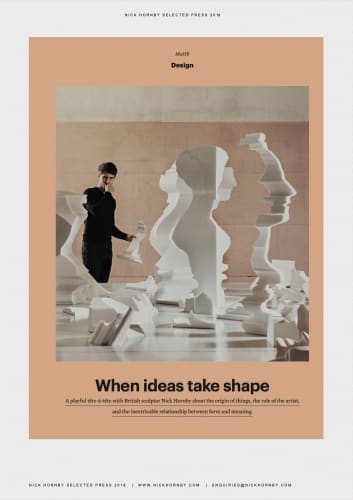

With hot drinks in hand, and the rarefied bliss of English sunshine warming our backs, we discuss the birth of his sculptures commissioned by MatchesFashion.com for 5 Carlos Place, the role of technology in creation and what constitutes ‘good art’.

E S Q : Why do you use technology in the creation of your sculptures?

NICK HORNBY: The reason I use tech—and there are lots of reasons—is because we are surrounded by it. And it is determining our lives. It’s like an inevitable subject. But in my case, it’s more to do with subjectivity and objectivity. So if you’re writing, you are able to quote someone. And you put it in inverted commas; then there is your voice and this other person’s voice. So within our history, a similar thing happens. Francis Bacon could do a painting after Van Gogh’s ‘On the Road to Tarascon’, where you know there’ll be this visual echo because it is the same painting. He just re-rendered the painting with his own style. But it’s undoubtedly a Francis Bacon painting. Not from Van Gogh. And that happens in every genre. Every medium and every historic moment.

E S Q : How does this apply to your creative process?

NICK HORNBY: In my case, I’m really interested in the beginning of things. Where do things come from? The Big Bang, what was before that? I’m sitting down and I have a white piece of paper. And I’ve got to make something, what do I do? So in the interim, what happens is that your head is filled with all these influences and echoes of things. You never really have that blank canvas. So I’ll make an object and it will be a composite of multiple different things. The digital enables me to remove the subjectivity of the human touch.

So I’m able to imagine a hypothetical situation where three things are combined. I can do that on a computer and produce a virtual object which is perfect. It has no flaws, imperfections of my making or gravity. Things can float, they don’t have to have any reality whatsoever. Then, somewhere from the concepts, I will transition it into the real world. And there are different gradations. So a 3D print somehow is a bit more real than something being modelled in clay. Or cast in bronze. Does that make sense?

E S Q : Because it is more perfect? Do you find that when you realise your perfect sculpture—that you have created on a digital program—into something tangible, it is a little bit disappointing?

NICK HORNBY: Actually, it is always a little bit more fun. And that I don’t really understand.

“I’m able to imagine a hypothetical situation where three things are combined. I can do that on a computer and produce a virtual object which is perfect.”

E S Q : Because there are surprises from turning ideas into creation? There’s serendipity in the process...

NICK HORNBY: I try not to deviate. There’s not a lot of spontaneity in the studio. For me the spontaneity is in the ideas. And from idea to reality, I tend to have chosen a path and I think I’m sufficiently aware of how it will turn out. So for example, if I am having something carved in marble, it’s going to be very close to the digitally modelled image. However, if I’m getting a sculpture hand- painted, then it’ll be a bit rougher.

E S Q : Would you call yourself a perfectionist then? You’re always starting from something that’s perfect.

NICK HORNBY: Absolutely not. Not at all. I’m not trying to make perfect art. I’m just interested in the concept of the transition from the virtual to the real. I don’t think either is a qualitative thing; I don’t think an object which manages to re-enact the concept is better than the one that doesn’t. I’m just interested in what that means to the viewer. For me the end game is to make something that is a bit liminal, a bit ambiguous, which is open. For the viewer, when you see my work, you’re curious. You are seeing echoes of things you vaguely recognise. Maybe something that looks like a 19th- century marble bust, a little bit like a cubist sculpture, then maybe a little bit like a shard or a space rocket. My job is to make something that is completely up to your imagination.

E S Q : You have three pieces here at 5 Carlos Place. What is the emotion that you are trying to create? Do you have that intention or...

NICK HORNBY: I’m British. (Laughs)

E S Q : Which is to say?

NICK HORNBY: One doesn’t have emotions.

E S Q : What?! (Laughs) Okay, where was the starting point then? Because these three pieces were commissioned by MatchesFashion.com for this townhouse.

NICK HORNBY: Right, starting point is easy. The starting is the site. One does their due research. Philip Joseph, the designer of the space. Epic legend. I like him very much. I remember when I got the gig, I googled him and found a video where he was asked about whether his work was traditional or contemporary. And he didn’t have the answer, which

I found quite interesting. I’m drawn to binaries that don’t really force binaries. Things that we perceive as being binary but actually are not. Anyway, I knew this building. It’s like Flemish renaissance; very ornamented, very decorated. Did you know that the street itself is fictional?

E S Q : As in Carlos Place?

NICK HORNBY: Yes, it was originally Charles Street, but it was rebranded as Carlos Place. The owner of this street wanted to vamp it up a little. So he rebranded it and filled it with high-end luxury retail on the ground floor and residential above, which is kind of what it is now. I’ve always been slightly interested in ornamentation and decoration in architecture. And how modernism clashed with high Victoriana. Long story short, the spiky sculpture that you saw on the second floor, we call it ‘The Shard’. It is actually the face of Michelangelo’s David, but it has been extruded to 8 feet and it overlaps on itself. So if you were to stand at one end and look down, you’ll see this face perfectly. It’s like a quotation in writing; there are two voices here: I’ve just taken the face of this very iconic David—arguably the ideal of human perfection—and rendered it in such a way that it looks like an extruded piece of architectural ornamentation.

E S Q : But you’ve hung the work so high that people won’t be able to look at it straight on to see the face of David.

NICK HORNBY: That’s not the plan though. The face of David is just the starting point. It’s not about the reveal. It’s not about like “ta-da, now you see it”.

E S Q : So it’s not important for you to reveal the origin story to the viewer?

NICK HORNBY: They’ll have their own origin stories. The meaning of the work isn’t derived from the artist. It’s not the artist that tells the meaning of the work. If I go look at Rothko, I don’t care why he painted it. I care about how it makes me feel that day. And what it means to me.

ESQ: Really?

NICK HORNBY: Absolutely.

E S Q : Because I always want to know the origin story. I feel it adds another layer to what the artist is trying to say. Which is always ambiguous.

NICK HORNBY: I think there is always an in-between. A piece of art, a piece of music, a piece of writing, it can definitely be enriched with narrative and context. But I think it is important that every time you add more, or every time you contextualise, or interpret, it isn’t reductive, and it’s not didactic. So if you look at a painting and there’s text next to it that says, “This painting is done at this moment by this artist and he did it for this reason”, it really wipes out the sensory opportunities for the viewer.

E S Q : As opposed to facilitating connection with a piece?

NICK HORNBY: I think it is possible to just to put out little satellites of thought that are sufficiently far apart for the viewer to then create their rhizomatic network of ideas.

E S Q : Is that how you would define good art? What is your definition of good art?

NICK HORNBY: Open. Not overly determined. Definitely, that’s very important. Good museums do the same thing. When you go to the Tate, it won’t say this is what this means. It will have a quote from someone famous like Ian McKellen saying, “I was inspired when I saw this, and I thought about chicken” or whatever. And that, I think, is more evocative.

E S Q : On a spectrum with ‘craft’ on one end, and ‘narrative’ on the other, where do you lie as an artist? Is it important for your pieces to demonstrate great craft? Or is it more important for it to connect with the audience?

NICK HORNBY: That’s a very good question. I will use two different words. So I wouldn’t use ‘craft’ and ‘narrative’. I’d probably use ‘form’ and ‘meaning’. And that is a real challenge. Let's say, I think the starting point is always a concept. It›s a theory, you›re having ideas. The point of it is the conversation. You are trying to have a conversation with the history, with your peers, with everything around you. So we start thinking of those ideas. The ideas somehow start to find their way into a form. You go from the virtual to the real. What happens is, as it’s going from to virtual to the real, and form turns up, then the materialities start to hold. Your idea might be to have a shovel floating in the air. Of course we have gravity, it has to sit on something. It either has a metal string or it has a metal pole holding it up. So then what happens is, you’re facing these material problems and you start to develop your own formal solutions. As you go on year after year, you start to develop a language in both. A set of ideas you are interested in and a set of formal solutions.

E S Q : What are your formal solutions to your ideas?

NICK HORNBY: My formal solutions tend to be monochromatic. I also like smooth surfaces. And those things have become my package. The dream is that the resultant object makes you question, not how did you do that, but what does that mean. That’s all that really matters and the level of fabrication is just a means to an end. It’s just the vehicle to try to keep it as open and interesting as possible. What do you think?

E S Q : I think it always has to be a connection; the meaning is key. Because especially in the world of art, anything could really be art.

NICK HORNBY: What sort of sculptures do you like?

E S Q : To be honest, I never really thought of what sculptures I like.

NICK HORNBY: If you guys went to a contemporary museum, are you more drawn to pictures, photos, videos...

E S Q : I am more drawn to pictures.

NICK HORNBY: That makes sense. As an editor, what you do is more narrative-based. But I’ve noticed by following you on social media that you like tech and you like materials. Because there’s a lot of material in the fashion world.

E S Q : I think art is supposed to inspire. Otherwise why is it there? When it comes to your medium, because it is sculpture, form must be important? As opposed to contemporary artists, which could just be a video playing in a room with scraps of paper on the floor. Form, or craft, is not as important as the meaning it’s trying to convey. Don’t you think?

NICK HORNBY: I can’t separate them. I’ll show you two examples quickly. [Whips out his iPhone]. So one them is Constantin Brâncusi. He’s a French dude. He made a sculpture called ‘Bird in Space’. And this is about 100 years ago. It’s the most phenomenal sublime object. It is made in polished bronze. And it is polished to perfection. It’s not about imagining a bird in space. It’s about the concept of what a bird means. He’s trying to find the epitome of this concept. What I find fascinating is when you look at it, it feels unreal. It feels almost virtual, because you can’t see any scratch marks, any blemishes. You just see yourself in the polished bronze. Of course, the fun contradiction is, that mirror-effect came about through the bronze being worked by hands. He made the form immaterial through its materiality, which I find very fascinating.

E S Q : And the second example?

NICK HORNBY: The other is Donatello’s ‘Mary Magdalene’ made from humble wood. I think it’s one of the most beautiful sculptures on the planet. It’s horrific to look at. But incredibly beautiful because of the pathos. I’m a complete atheist. Can’t bear religion, but this woman who was a prostitute, and Jesus loved her and she went to the desert for 40 days. And this is the moment where she has just come out of the desert. We could all relate to this story of a wretched humble person, who has had this transformative experience. I’ve chosen these two pieces because one of them is clearly sexy as hell, beautiful, stunning and immaterial. And the second is on the other end of the spectrum. But both of them have

the relationship between concept and form as inextricably linked. Does that slightly challenge some of your thoughts about the connection between these two things?

E S Q : A little bit, but they are both still sculptures. Again, with contemporary art, it could literally be a brick in the corner of a room. And that’s art, you know what I mean? No craft really. But it’s more about the story.

NICK HORNBY: Rest assured, my pieces are a real fucking pain to make.

E S Q : I can see! (Laughs) And you use quotes to name your work?

NICK HORNBY: I just named a piece this morning with a quote from Coco Chanel: “I never want to lean more heavily on a man than a bird”, and one of the sculptures in 5 Carlos Place is called, “Vanity working on a weak head, produces every sort of mischief”, and that’s a Jane Austen quote. I like to find a quote that just happens to fit perfectly with my work.

E S Q : It imbues new meaning into the work, I feel.

NICK HORNBY: I think it does, yeah.

E S Q : Tell us more about the pieces for 5 Carlos Place. Is it a statement about fashion being all about vanity?

NICK HORNBY: The black sculptures in the stairwell are composites of 19th- century marble busts found in the V&A. And each one comprises three different heads. In the V&A, there is this court that is filled with busts. When I first went, I was really fascinated by the two different styles. One style is very idealised, while the other is more realistic. The landed gentry, the people who inherited lots of money and wealth, they wanted their busts to be very classical and idealised. Whereas the people who had made their own money—the lawyers, there was also a surgeon—they wanted their faces to be recognisable. They didn’t want it to be just their name and their house. They wanted people to look at the busts and go “That is XYZ”. And I found that fascinating. What I did was I took each head that fitted in with that narrative and I clustered them together. So I’ve made a series. It’s supposed to be a portrait of an archetype, rather than a portrait of a single person.

E S Q : What is the best conversation you’ve ever had with someone about your work?

NICK HORNBY: Ah, I love when people say, “Oh my gawd, I can see an elephant.” (Laughs). People are funny. You have fascinating conversations with people who are in the art world and with people who are not in the art world. If anything, it’s more fascinating to talk to people who’ve been all over the world; they bring such extraordinary things. You’re much more refreshing to talk to than some art person.

E S Q : Do you think good art should either reveal the artist or conceal

the artist?

NICK HORNBY: The artist is irrelevant. What matters is what you get from the work.

E S Q : You’ve never thought, “I’ve put so much of myself in that piece”?

NICK HORNBY: I put nothing of me into my art. But in fact, all of me is in there too, but you can’t access me. You only access me through my life. I’m just contributing a small component to this big project, which is visual culture. And it would be really narcissistic for me to feel like I, as a person, need to be present in my contributions to the bigger project. In a party, I want to have some fun. But in a gallery, I want to be contributing in a serious way.