MA Show: Chelsea College of Art, London

Of course, all that is solid melts to air. ‘I hope that they are readable as purely formal objects’, states Hornby, gesturing towards Untitled, after Brancusi...

Untitled, after Nick Hornby

A review of his MA final exhibition at the Chelsea School of Art

19th - 23rd of September 2007

Brooke Lynn McGowan

In ‘Restitutions of the Truth in Pointing’, a text originally conceived for the Musée Louvre, Jacques Derrida queried, ‘Why always say of a painting that it renders, that it restitutes?’ The theorist continued: ‘it’s a matter of knowing from where they return [...] if it’s a question of knowing what revenue is produced by their out-of-service dereliction, what surplus value is unleashed by the annulment of their use value’. Though the question in this case addresses painting, it is no less appropriate to the art and artworks of Nick Hornby, on the occasion of his MA final exhibition at the Chelsea School of Art, which took place, on site, from the 19th to the 23rd of September. The terms of inquiry however, must be changed. It is not a matter of knowing ‘from where they return’, but rather to what they return. At once celebrations and citations of differing images of the future, modernist aims towards an ideal, each of Hornby’s objects render and return the subject to the seemingly austere space of the object. Confined by their intentionality, Hornby’s works stand at the centre of a pastiche of at once merging and divergent forces. As much formal objects as citational forms, each of the artist’s pieces composed in what must be understood as an installed—and just that— composed space exist in their own becoming-archive, at the centre of a process of determination and discovery, where what cannot be escaped, is what always returns within the work and outside of it: ‘outside the picture, inside the picture, and, third, as a picture, in their painting truth’.

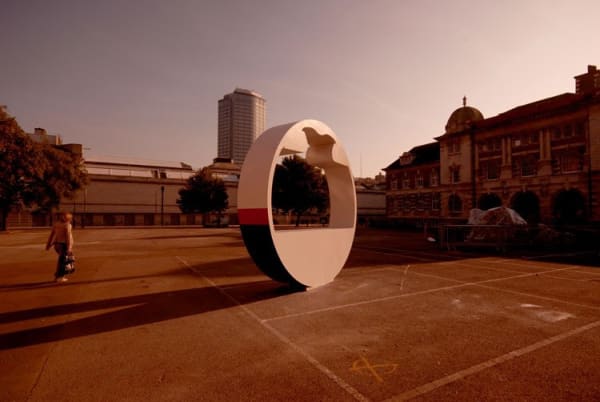

The adherent authorship, the intentional subjectivity of the artist, which cannot be escaped in Hornby’s work, is not immediately evident. When entering a gleaming white space on the first floor of the school, one is met first by large spirally structure, sized a few inches taller than Harrison Ford. On the adjacent wall, a one minute and fifty-two second clip from Star Wars: Empire Strikes Back plays on loop, with the image of the seeming same structure at the centre of the image. In quick succession, in the centre of the room, the viewer then meets with two further objects, together presenting the three centrepieces of the installation: Untitled, after Brancusi, the seeming presentation of single Victorian table leg on a white plinth, and Untitled after Hans Arp, an large and incomprehensible form, boxing, tilted, and unyielding—and like the two previous sculptures and the space itself, gleaming bright white.

And indeed, the space itself is important. ‘I re-plastered all of the walls to make them perfectly pristine and white’ says the artist. The intuitional structure of modernist hegemonic space is undeniably an underlined structure within the image-making process of Hornby’s exhibition—installation. For if the white space introduces the safe conception of the museal or gallery space, in which object, found or otherwise can, in its 'out-of-service dereliction', accumulate value, it is in fact this process of presentation and performance of an object which Hornby addresses. Each object in the room is performed as part of a process of discovery on the part of the spectator, who having first perceived the three primary sculptures in the room as independent modernist forms, come to them understand them as much more: as ‘specific objects’ perhaps in their right, unitary forms, but also, as the distillation of a personal and at times political process of intention.

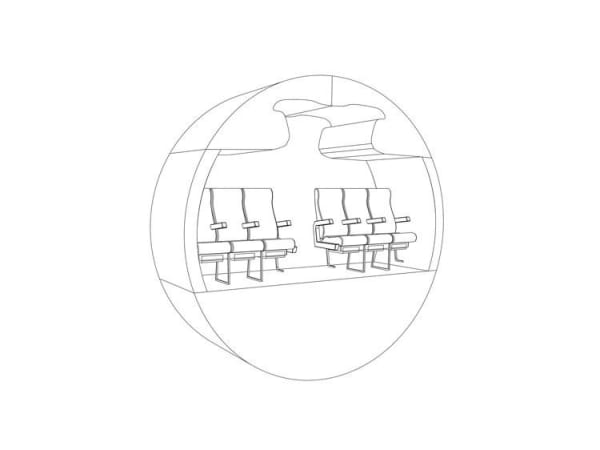

‘It is a glyph for globalisation’, says the artist, pointing towards Untitled, after Hans Arp, the massive and uncanny stone white and freestanding Boeing 727 Locker Compartment. ‘I was always interested in airplanes, little inscriptions you see in the sky, distant, far away. If you are close to them, you experience them not as object, but as a vessel. You can never really touch them.’ The symbol stands in for the abstract weight of systems of global displacement, out sourcing and transnationalism that greatly effect the lives of each one of us, and yet, are at once as material and dematerialised as the airplane itself—just beyond our reach: heavy, and as light as air.

Of course, all that is solid melts to air. ‘I hope that they are readable as purely formal objects’, states Hornby, gesturing towards Untitled, after brancusi, whose sweeping linear shape is intended, by the artist, to reference Brancusci’s elegant and untouched sculptures as much as it does a turned Victorian table leg. Standing alone, enshrined on a white plinth, the object is echoed throughout the space. A large print of the object can be found on the wall. In the far corner, a table, supported by like hand-hewn Victorian legs stands. If what is at stake in the work of art in an era after the dangerous reproducibility of the image or production of the object is the potential loss of its ‘aura’, its reduction to the banality of the copy, then Hornby’s work addresses this peril by reproducing it, by instituting a perilous repetition of the image and the object, underlining the tension between the perceivably manufactured item (i.e. a table leg, any table leg) and one that is in actuality, hand made, with the aid of mechanical reproduction. Lying casually in the corner of the room, a stack of photographs testifies to the process of producing these objects. Each one was made by hand, carved in plaster, through the misuse of the front axle of Hornby’s father’s car. Indeed, if capitalist dissolution enacts the invisible hand, it is shear visibility of process in the artist’s work—a crack running the length of the side of the singularized leg, the imperfect grooves revealing where the object had once been attached to an automobile—which cites the hand which hand which cannot be removed. The intention that cannot be denied. The subject which returns, ‘slowly’, says Derrida, ‘but always too quickly.’

© Brooke Lynn McGowan, 2007, Miser & Now

Artist’s Statement

This project brings together a series of three objects: a prop from a star wars film recreated in plaster; a Victorian table leg, turned by mis-using a VW Polo as a lathe, and a section of a BOEING 747: As sculptures placed on the plinth, they evoke the art of the 1980’s or of early 20th century modernism, but do so only as the by-products of a convoluted practice of research and making.

In Mythologies, Roland Barthes set up a dichotomy between the abstract - the “superlative object” with its “perfection and absence of origin”, which looks as though it has “fallen from the sky”, and its opposite: “the technical and typically human operation of assembling”.

This series of objects forces those dichotomous ideas of assembly and autonomous objecthood into an awkward dance: the abstraction here is an accident of construction, the whole is only a part. A cross section of the overhead luggage locker of a passenger jet mimics the integrity of 20th century abstract shape making.

Star Wars is a charade of completeness: computer graphics, model-making, and live action stitched together in the edit to create a seamless, transcendent reality. By casting the prop in plaster, by isolating and repeating the video, the seams of this reality are unpicked, the whole disintegrates into its constituent parts, only to reform again, as the video begins, and the spiral turns.

A turned table leg is presented and re-presented in the space: now above, and now below the plinth; first held aloft as object and icon, then – literally – put back in its place, recalling Brancusi’s Bird In Space, that ultimate example of Barthes’s “perfection and absence of origin” and simultaneously mimicking the visible and prized craftsmanship of the Victorian furniture maker.

The objcts are surrounded by, and the viewer teased by, these competing versions of their own histories: an immiscible series of provenances, explanations, and origins, in diagrams, repetitions, stills and video, which overlap and contradict one another, conflating origin and destination, process and product.

These are miscreant objects, misquotations, creating abstraction out of utility, disguising craftsmanship within mechanism, art history within the instruction manual, and pitching the integrity of objecthood against process and play and hazard.